The Social Contract

“Since no man has a natural authority over his fellow, and force creates no right, we are left with agreements as the basis for all legitimate authority among men.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau – The Social Contract

The theory

of contractarianism can be found mainly in the works of Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques

Rousseau, John Locke, and Immanuel Kant. I will focus here on the theories of

Hobbes and Rousseau in order to unpack what is the social contract and how this

links to theories of Natural Law, the State’s legitimacy, how it requires

consent as its basis, and whether this social contract actually exists.

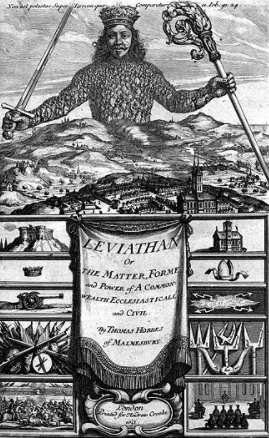

HOBBES

The political

philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who lived in the sixteenth century, accepted the

philosophical argument of the day that a person’s highest duty was

self-preservation. Therefore, according to Hobbes, the state of nature is a

condition of perpetual turmoil between disconnected, competing individuals. It

makes sense that the state of nature was for him a state of war, as the highest

duty was not morality, but precisely the lack thereof: purely animalistic

survival. Hobbes focused on the selfishness and

competition between men because he was describing the bourgeois man of an

emerging capitalist society and stripping off him any type of civilisation. It

is wrong, some argue, to depict men before civilisation as purely self-interested

and antisocial, as nature provides multiple examples in which it behaves in a

cooperative and harmonic manner. If, on the contrary, one perceives the nature

of men to be also a moral and cooperative one, the (state) Leviathan does not

seem a viable means for peace but one of submission in which freedom is effectively

taken away from people. This counter-argument depends then on the evidence

found in pre-historic communities for example, it could not be based on, as

Macpherson rightly proposes, an extraction of the main traits of men who are

already used to living in a highly competitive industrialised world. And even

in those, there are multiple examples of cooperation amongst men. Moreover,

without those, no civilisation would stand the test of time.

According to Hobbes,

the ‘self-preservation instinct’ is responsible for both social scenarios: war

and harmony. This survival instinct drives men to take from others whilst

creating ‘a war of all against all’; however, it also drives them to cooperate

with one another by agreeing in a common coercive power. Consequently, there

arises a contract between rational beings in order to keep peace and preserve

one’s life; it is a purely economic exchange of which we can all theoretically

benefit.

A ‘covenant of every

man with every man, in such manner as if every man should say to every man, I

authorise and give up my right of governing myself, to this man or to this

assembly of men’ (Hobbes, 2014:134).

Hobbes clearly started

from the assumption that 1) morality is something that emerges after we are out

of that state of nature, with the association; and 2) the right of governing

oneself not only leads to state of war but has to be given up in order to get

into the contract with others.

The idea that there is

no morality before the contract has the implication that each contract keeps

changing and evolving as morality is created with it and vice versa, as it

annuls the idea that there are overarching laws or principles by which we are

all governed, leaving it to the sovereign to decide. But this is moralrelativism at its highest since when morality is placed on one person alone, it

loses its meaning. There is an overarching morality and it can be discovered but

it does not depend on one sovereign and it is discovered by all of us individually

and within ourselves only. Therefore, we reach an important question, is man

only free when he is chained in order to suppress his inner selfish desire? Or

can men transcend or transmute that selfish desire and turn their existence

into a moral one?

The covenant emerges

then when one knows that everybody else has done the same, leaving like that

the ‘monopoly of force’ to the state. It is, therefore, argued by Hobbes that the

lesser opinions on how to defend the country, the lesser division on how to

proceed. In this unified and single-headed form of government, internal

conflict is reduced and ‘peace’ takes place. Hobbes was clearly advocating for

an absolute sovereign that could not be questioned nor challenged by the common

man. A contracting man exchanged his natural rights for protection and security

but he preserved the right of self-defence because without it the contract

would not make any rational sense and because, according to Hobbes, that right

does not pose a challenge to society’s peace. Consequently, the attainment of

peace demands that no one “resists the sword of the commonwealth in defence of

another man” (Leviathan, 169); prohibiting like that collective resistance.

ROUSSEAU

Rousseau’s

thought was quite the opposite to Hobbes’. They both started from different

premises about the nature of man. In the state of nature, people were

completely free but, instead of Hobbes’ state of war, Rousseau thought that people

lived in abundance because of their simple lives. As civilisation developed and

populations increased, men had to share nature with a lot more people and there

was competition between us. People became inextricably interdependent and with

that came the separation of labour and the distinction between social classes,

what degenerated in chaos and conflict. Therefore, Rousseau’s assertion that “men

are born free but they are everywhere in chains” expresses this evolution from

natural freedom to civilised slavery.

The

philosopher thought that for society to function there would need to be laws to

keep peace and harmony. But if the sovereign holds absolute power, that would

soon be to the detriment of the people and their natural rights, thus rendering

the contract useless for those people. If the ones making the laws are the same

ones in power, it is highly likely that they will pass laws to favour their own

interests instead of the interests of the whole. We can already see that the

main consequence of starting out from different premises on the state of nature

is where will we find morality to be located. According to Rousseau, exchanging

survival for protection removes all kind of morality from people’s actions. He

writes:

To renounce your liberty is to renounce your status as

a man, your rights as a human being, and even your duties as a human being.

There can’t be any way of compensating someone who gives up everything. Such a

renunciation is incompatible with man’s nature; to remove all freedom from his

will is to remove all morality from his actions. (The Social Contract, 4)

Subjecting the will of the

self to the community’s will is dangerous precisely because we would be starting

off by subjected and not free individuals and… can individual slaves compose a

free collective? I’d say quite the opposite, only free individuals can make up

a free society. This is, in my opinion, a crucial flaw with contractarianism. If

morality is not prior to the collective (or any type of) contract, there can be

no freedom. Freedom and slavery are both manifested within and without oneself,

and individuals enslaved by their own passions, fears, desires, etc,. can never

produce freedom outside themselves, not to mention create a free collective.

To say that a man gives himself to someone else, i.e.

hands himself over free, is to say something absurd and inconceivable; such an

act is null and illegitimate, simply because the man who does it is out of his

mind. To say the same of a whole people is to suppose a people of madmen; and

madness doesn’t create any right. (The Social Contract, 14)

Rousseau was, therefore,

disposed to find a formula for a form of association that allowed individuals

to maintain their natural rights and thus be free, while uniting with other men

with the purpose of protecting their goods and mainly those same rights. This

would be a way to maintain the social order while avoiding doing so by force.

He writes: "the social order isn’t to be understood in terms of force; it

is a sacred right on which all other rights are based. But it doesn’t come from

nature, so it must be based on agreements." This is so because if we understand

nature as everything, we would have to include the possibility of erring, of doing

wrong, and that disturbs the social order. Man is the only creature that has the

option to choose whether to do good or evil. So, it is an individual choice

that stems out of the individual’s free-will what allows the social order or

what disturbs it. And this, paradoxically, is what I call Natural Law, it is

the ability of men to understand and subject themselves to the natural forces

governing this world and to choose the right path. The social order therefore arises

out of each individual’s agreements with others; as disagreements will provoke social

chaos. This polarity is found everywhere in nature. But the social contract

varies from tribe to tribe, from town to town, from state to state as it is

based on customary understandings of right and wrong.

We can see there that the covenant

is not natural, it arises out of the free will of each individual man, and

because of that, it can be dissolved. The choice is morality, and that is

natural, the outcome of that is man-made and thus it starts being a mirror-like

version of nature which has its time and place but which has an expiration date;

as further away it gets from nature closer it gets to deteriorate and finally

disappear. But men seem to have a hard time with the idea that nature is

cyclical, that there is life and death constantly everywhere one looks. Death

is just a part of life, the matter decomposes and it serves for the soil to be able

to grow new life. These are the patterns we see everywhere and, although men try

to go against it, it is a real law and cannot be broken. Anything we do that

goes against nature is doomed to fail. Rousseau claims that:

In order “to protect the social compact from being a mere empty formula, it

silently includes the undertaking that anyone who refuses to obey the general

will is to be compelled to do so by the whole body. This single item in the

compact can give power to all the other items. It means nothing less than that

each individual will be forced to be free.” (The Social Contract, 8)

This oxymoron

presents perfectly the main problem with the social contract theory. If one is

born into imposed man-made unnatural rules, those are going to be necessarily in

contradiction with those natural laws and our nature as natural creatures, and that

is something that we cannot avoid even if we tried to. So, we are forced because

this contract is done when we are babies and when we do not object or work in

order to change the social contract in adulthood. It is never a consented contract,

and so it is neither an agreement, because we are born into it and we are “forced”

to be part of it. The best representation of this is the birth certificate, as

it is the bond that is created by the state that keeps us in bondage with the

collective “public”. The idea that what we are unwillingly signing up for is “to

be free” would highly depend on what we mean by freedom. For Rousseau, as

opposed to Hobbes, the requirement that individuals governed themselves was crucial

if those were going to have to willingly enter into the agreement. And however idyllic

direct democracy sounds when reading Rousseau, history shows us that the collective

can be far more dangerous as people are indeed subjecting their responsibility

to govern themselves to the collective imaginary governing them.

It is

forced precisely because, at the micro level, I cannot bind you into an

agreement with someone else; either you enter into the agreement yourself

willingly or it, by definition, is not an agreement. So, at the collective

level, the state cannot force anyone to enter into a contract, it can also not force

the social contract onto free beings. That is why the state creates the “creatures

of state” which are called persons and which are subject to codes, statutes and

regulations. These are entities which are effectively slaves and which work for

the state. Because they are mere abstractions, the state has power and control

over them. No fiction can have control over natural men, but fiction can have

control over its franchised fictions. Therefore, as long as natural men

identify with the fiction and allow themselves to be subjected to the will of

the state (or sovereign), it is a consented contract and it falls under the

category of a seemingly “valid” social contract. But if men discover that they

are free and that they have always been and that they can free themselves from

the will of the collective by simply stop identifying with the fictional entity

and start taking responsibility for themselves and thus stop needing the state

to act as a father for them, then they shall be free from the agreement-bondage

made upon them by their forefathers.

If one thinks about the

social contract in those terms, it makes much more sense. People who are not

willing to take liability for themselves can keep being chained to the state’s

privileges and duties as good citizens. Those who wish to live their own lives

according to higher laws above men have to undergo a process of understanding,

meditating, cultivating, etc… A process of working on their fears, their

conceptions of love and right and wrong and like that to be able to break free

within and thus without too. These beings will not pose a threat to the peace

of society because they have understood why those mechanisms are there, how men

can actually become a wolf to men, as Hobbes would say, and with that knowledge

collaborate on the collective growth instead of the collective destruction.

Maxim of Law:

Non videntur qui errant consentire.

He who errs is not considered as consenting.

Contract Case Law:

"Every mean is independent of all laws except those prescribed by nature. He is not bound by any institution formed by his fellow men without his consent" Cruden v. Neale ZNC 338 May Term (1796)

"Failure to reveal the material facts of a license or any agreement is immediate grounds for estoppel" Lo Bue v. Porazzo, 48 Cal.App.2nd 82, 119, p.2d 346, 348.

"Waivers of fundamental Rights must be knowing, intentional, and voluntary acts, done with sufficient awareness of the relevant circumstances and likely consequences." U.S. v. Brady, 397 U.S. 742 at 748 (1970); U.S. v. O'Dell, 160 F2d 304 (6th Cir. 1947)"

Unconsciable "contract" - "One which no sensible man not under delusion, or duress, or in distress would make, and such as no honest and fair man would accept." Franklin Fire Ins. Co. v. Noll, 115 Ind. App. 289, 58 N.E. 2d 947, 949, 950.

"Party cannot be bound by contract that he has not made or authorised" Alexander v. Bosworth (1915), 26 C.A. 589, 599, 147 P.607.

The fraudulently "presumed" quasi-contractus that binds the Declarant with the CITY/STATE agency, is void for fraud ab initio, since the de facto CITY/STATE cannot produce the material fact (consideration inducement) or the jurisdictional clause (who is subject to said statute).

"The term "liberty" ... denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to aquire useful knowledge, to marry, to establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience… The established doctrine is that this liberty may not be interfered with, under guise of protecting public interest, by legislative action." Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399, 400.

"The right to be let alone is the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilised men. To protect that right, every unjustifiable intrusion by the government upon the privacy of the individual, whatever the means employed, must ne deemed a violation of the Fourth Amendment" Olmstead v. U.S., 277 U.S. 438, 478 (1928).

"Both parties to a contract must agree to its terms and to be bound in legal relations. The corollary of that is that one person cannot unilaterally impose a contract on another." Silver's Garage Ltd. v. Bridgewater (Town), (1970) CanLll 196 (SCC)

Comments

Post a Comment